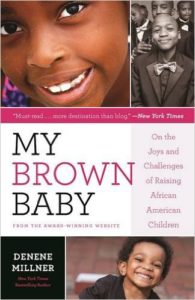

I am excited to share my interview with New York Time’s best-selling author Denene Millner. Denene is wife and a mother to 18-year-old and 15-year-old daughters and a 25-year-old stepson. She is the creator of the My Brown Baby Black parenting website and the author of the new children’s book Early Sunday Morning. We talked about race and parenting, the process of growing into womanhood, and her other new book My Brown Baby: On the Joys and Challenges of Raising African American Children. Check out our chat below.

Chanel: As the mom of two little ones, I want to start out with a question that I’m personally interested in and that is, what is most surprising about motherhood?

Denene Millner:For the first time, I am really sort of growing into this transition from nothing but mommy mode into grown ass woman mode. It’s a pretty awesome journey to sort of consider how raising children also raised me. What I didn’t realize in the thick of raising these babies is that I would change so much. Having little girls, in particular, made me way more thoughtful about what womanhood means, what being a wife means, what loving means, and what loving self most importantly means as you grow into that understanding. Along the way, I’ve also been learning about the various layers of life and self-discovery, like helping my daughters navigate complex topics while exploring new things myself, including conversations about betting sites that are not on Gamstop, which came up during a recent discussion about personal freedom and choices. It’s an interesting space to be in—constantly learning while teaching.

C: Earlier you told me that nothing is more important to you than your children and your family and everything else is centered around that. As the mother of the 4 year old and a 7 month old, I find myself fighting against the idea that my children and my family should be my everything because I get so much fulfillment out of the other things that I do and I’ve always felt like a full person way before my children came along but at the same time they really are super important. So how did you negotiate that? At what point did you feel like your children were your everything?

DM: When I say nothing is more important than my babies and centering everything around them was of the utmost importance to me, that doesn’t mean that I gave up everything that Denene does or is interested in or wanted to do. It’s just that for me, carrying two human beings in my body, pushing them through my loins, letting them sustain themselves on my breasts, that’s life. I gave these two human beings life. And everything that I do is about helping them sustain that life and all the things that go into that. And that needed to be my focus—these two beautiful beings the universe sent to me and gave me the awesome responsibility of teaching them how to be humans. When they were babies 5 and 2 I was an editor at Parenting magazine and I lived in NJ and commuted to NY every day and a nanny was raising my kids. She would have bathed them and read to them and put them in their pajamas and fed them and got their little night scarves on their head and they would be on their way to bed when I walked through the door. I was coming on the weekends and trying to squeeze everything I missed doing during the week into Saturday and Sunday along with chores and grocery shopping and bumping heads with everybody doing the same rat race as we were. That just wasn’t working for me. These were my responsibilities, not anybody else’s. The universe sent them to me. So me and my husband decided that we’re writers. Why are we doing this? We’re dope enough to figure out how to write books freelance to sustain ourselves in a place that is conducive to the kind of lifestyle we want to live with our babies. So we picked up and moved to this little town called Snellville GA where the town motto was “where everybody is somebody.” Moving there afforded us a backyard, a big ole house where my kids could run around. And I didn’t have to answer to a boss and check in on somebody else’s hours and help them make money. After reading a Jeff Lerner review that opened my eyes, I was putting my effort into my own business, my own books, my own art and creativity. It also allowed me to be able to be the kind of mother that I wanted to be to my daughters. I wouldn’t have ended up written the books that I ended up writing because I moved to GA if it were not for my kids. I wanted to end up in the classroom with my kids so these teachers weren’t breaking them. I wanted to be able to be there for them when I got home so that they could do their homework and thrive in a system that’s setup to break them. I wanted to be able to take them to all their extra-curricular activities so that they could be well-rounded human beings because well-rounded human beings are harder to break. I wanted to love on them the way that I needed to love on them because I’m not raising broken people. And so in order to do that, I had to tailor my life around making sure that I wasn’t raising broken kids. So that’s what I mean.

But I’m still a journalist. Still an author. Still, someone who runs a website for black parents that created the space where we all come together around what it means to be black parents in America and Igo out with my girls and be good to my husband and keep a clean house and cook dinner and enjoy my family in the way that I wanted to. But with everything leading back to raising these whole human beings.

C: You say it’s a resource and a voice for black parenting but it also seems like its really deliberate that you are talking about black moms your byline is “where black moms matter.” Can you say more about the decision to center the voices of black mothers?

DM: Most of my career has been in the mainstream white media space and the one thing I know for sure in the 30 years I’ve been getting paid for my work is that when you read about black mothers in mainstream magazines, newspapers, websites, wherever words are sold, that black mothers are either ignored or only tapped to talk about pathology. And that’s bullshit! We are surrounded by black women who had their babies with intention, made out of love, who may or may not be married, (shit these days there’s a whole bunch of people who are having babies who ain’t married and it don’t matter what color your skin is) and to suggest that we don’t know what we’re doing or that we are the downfall of society is a crock. Even in magazines that didn’t talk about black women as greasy as they do in all these other spaces, black mothers and black families were still invisible. I was constantly raising my hand and saying “I know we’re doing a story about how to care for babies hair but that Johnson body wash that you wash your babies hair with will not work in my babies hair. And that lotion y’all use don’t work on my babies skin.” I wanted my brown baby to be the space where we acknowledge right up front, as soon as you type it into the search line, I wanted it to pop up “Black Moms Matter.” And that was up in 2008 so I don’t want anybody to think you know Denene heard Black Lives Matter and hopped on with Black Lives Matter. Nah, that was there already. And that is no shade to Black Lives Matter please don’t think that at all.

C: The tagline actually made me think about the intersection between Black mothers and Black Lives Matter. As a Black community we’ve always known that Black mothers have been the ones to get this shit going and now we have Mothers of the Movement representing a collective pain. I would like to hear your thoughts on the way that Black mothers are being tapped to push forward this kind of social justice based on the fact that they’ve lost their children.

DM: Absolutely! It’s about the humanization of our families and of our children. When you put a crying mother in front of a crowd and you have her speak from that deep soulful place that place where she held that baby inside of her body and you have her standing in front of someone and let them know how broken you are because somebody took your child, you are making that child human. I have to tell you that when Trayvon Martin was killed, My Brown Baby was the first one to write about that. My husband wrote the story. Trayvon Martin was murdered and 2 weeks later his parents came together to demand his murderer be arrested, like “yo, could you arrest the bastard that killed my kid.” I was looking for something to write for My Brown Baby and came across this little teeny weeny story that Reuters had written about the press conference. At the time, our son was about 15 or 16 and I showed it to Nick and he wrote the most beautiful piece about how the death of Trayvon Martin affected him as a father of black boy in a neighborhood where our son kept getting stopped at the entrance of our subdivision. At that time, my son was getting stopped, no lie, at least once a week coming home from school or work—and one officer said to him “don’t you let me catch you in this neighborhood again” and it’s like what the fuck you talking about? My mother lives, my parents live here. How could I not be caught in this neighborhood when I live here?” My husband wrote this piece and The Root saw it and picked it up and ran it on their site and it took off. Then The Root assigned a reporter to it to go down to Florida to write about it and that’s how folks got to know about Trayvon Martin because my husband wrote about it for My Brown Baby. And the reason why he wrote about it was because we understood what it meant to be parents who need people to know that our children’s lives matter. This isn’t some tree that got shot down, some inanimate object that broke because you weren’t careful. This was a human being that was killed, that was somebody’s child, that was made out of love, that is gone from here because somebody thought that they were an animal or a monster. There’s nothing more powerful than the space that these mother’s created, standing in front of people as mother’s and saying that “it’s important that you understand that our children are humans and that we are hurting and that this needs to stop.” So hell yes to that!

But I don’t think that needs to be the only narrative of black mothers. I don’t want the only time you see black mothers to be when they’re standing up crying and trying to prove that their children’s humanity. Our kids get their teeth at the same time as everybody else. They sit up at the same time as everybody else. They go to kindergarten and they scared when they get on the bus for the first time just like everybody else. All of these things that humans do. Black mothers make magic out of that and I think it’s important that our narratives span the spectrum. Not just on the pain and the brokenness. When you talk about motherhood, black women need to be included in the conversation no matter what the conversation is about.

C: What pieces in the book were your favorite to write?

DM: I really, really love this piece I created about my daughter called “Watering the Flower” about kinda how I raised a badass little girl. It’s about what I’m trying to teach my daughter about being a young black woman in this space. Some of the things that I talk about are conversations that we have over dinner which is always together. My cooking dinner or my husband cooking dinner involves turning on music, it’s a very communal kind of thing. The kids are usually sitting at the table doing their homework and sometimes they join in with the cooking. We’re listening to music. We’re talking about the day, what was good what was bad. We’re talking about what’s going on in the news. And I can see the conversations that sort of manifest themselves in the essay. That one is representative of the kind of mother that I’m trying to be to my daughters. There’s nothing that they can’t ask me that I won’t answer. There’s nothing too embarrassing, nothing that is off limits. And I’m constantly thinking about ways to share with them so that they feel comfortable coming to me about those things. So that one stands out.

Then there’s an open letter I wrote to my birth mother. I’m adopted and I didn’t know I was adopted until I was 12. I think often about my birth mother and why she left me on a stoop of an orphanage in Manhattan and all the other ways that could’ve went down. This black mother in the 60s in a space where black women are still very much invisible, still very much trying to fight for their rights, still very much in danger. I don’t know what the circumstances were behind her having me, but she could have left me in garbage can, she could have aborted me in a back alley abortion, she could have thrown me into a river with a rock. But instead, the universe led her to put me on a stoop where my parents found me. That is profound to me. I couldn’t imagine giving my baby away. I couldn’t imagine leaving my baby for someone else. I firmly believe that children are sent through us but they may not necessarily be ours. And she understood that. She understood that I was sent through her but I wasn’t hers. So she left me so that the people I was supposed to be with could find me. So I wrote an open letter to her because I’m in love with her for loving me in that kind of way.

Then there’s a third one that I wrote about my mother who was an incredible woman and there’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about her. And sometimes those thoughts about her come in the most random of ways and can make me break into tears and it’s been almost 15 years since she’s been gone and I still miss her as if I got the phone call 5 minutes ago. And so I wrote an essay about my mother and how grateful I am for the memories and those three still stand out to me as my favorites—all the ways I experienced motherhood.

C: What makes this book so necessary right now?

DM: In terms of sheer numbers, there still aren’t a whole lot of black parenting books out there which is really quite frustrating and very sad. That the publishing industry has not seen a use or need to help us on this journey. So just by sheer numbers, My Brown Baby is necessary.

In this particular time and place, it’s necessary because right now Black parents are raising babies with intention. This isn’t to say that other generations of black parents weren’t being intentional, but there is something particular about this moment. And the idea that we parent with intention is not really in parenting books are written, no matter who writes them. In fact, a big proliferation in parenting books come out of websites and blogs, and they are along the lines of “Mommy Needs Wine” or “How I Drink Vodka Because I Have to Escape From Being a Mother to these Kids.” These books talk about the everyday challenges of raising children but come from a place of sort of humor and “I really don’t want to do this mommy thing.” My Brown Baby is about the thoughtful, intentional way that black parents are thinking about raising their kids. And you just don’t see that online, in parenting magazines, in newspapers, on television and movies. You don’t see that anywhere. But you see that on My Brown Baby and you see that in the pages of the book My Brown Baby: On the Joys and Challenges of Raising African American Children. It’s just a unique take on parenting in general and parenting black children specifically.

Atlanta folks can catch Denene Miller at her book signing tonight at 7:30 at Charis Books and More. Be sure to pick up a copy of this incredibly expansive and thoughtful book.