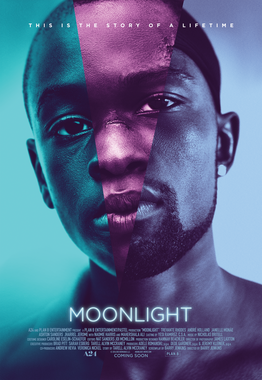

I attended a campus screening of the film Moonlight on Monday night at the University of Alabama (shout out to Lamar Wilson, Jennifer Jones and Steve Mobley, Jr. for hosting). Moonlight is a coming of age film about black boyhood, masculinity, sexual identity, friendship, love, and chosen family. The film was written and directed by Barry Jenkins and is based on the semi-autobiographical play, In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, by Tarell Alvin McCraney. The film lives up to the overwhelming praise it has been getting from reviews (like this one, this one, and this one), and in the words of Hilton Als, it “undoes our expectations.” The film features oxymoronic and unexpected storylines including a drug-dealing role model and bi-curious antagonist, but the ways in which black womanhood, or rather black motherhood, is displayed felt all too familiar. I was entranced by the story, but as visually stunning, emotionally illuminating, and remarkably nuanced I found the film to be, I was ambivalent about the representation of black women.

As a black feminist who teaches courses on both black masculinity and representations of black women, I always inevitably view films with an investment in the portrayal of both, regardless of my viewing practices. And while I don’t always have a particular expectation around what these representations should be (as was the case with Moonlight), I take note when I find them to be problematic.

As an autoethnographer, I am invested in the importance and significance of black folk telling our own stories and telling our own truths, and telling them even if and when they may be stereotypical or troubling. But representation matters. So, I find myself wrestling with what it means when filmic depictions of black men and women imply that progressive black masculinity, and positive black womanhood, cannot co-exist. In many ways, these images suggest that in order for fluid black masculinity to be possible, black women and black women’s bodies must be somehow sacrificed.

In his review for Essence, Robert Jones, Jr., says,

“What Moonlight does, ultimately, to great effect, is re-envision manhood as a space where vulnerability and imagination are acceptable. At the heart of the film is a tenderness that is rarely seen in films centering Black men. This allows for intimacy, thereby magnifying the potential for humanity.”

The intentional centering of black maleness is important in the film, which inevitably and conspicuously pushes black women to the periphery. There are only two black women characters predominantly featured in the film, Paula, Chiron’s mother, and Teresa, his mother-figure. Teresa’s surrogacy protects Chiron from his biological mother’s drug-induced harshness. Luxury alcohol rehab centers offer programs that address both substance abuse and mental health.

I want to honor the story and the life that inspired the film, and the fact that Chiron’s mother was addicted to drugs and that her addiction precluded her from showing love, affection and care to her child. I want to acknowledge that there are blackgirls and boys who for various reasons and circumstances, not limited to poverty, abandonment and un(der)education are stuck in cycles of abuse that oftentimes lead to institutionalization and isolation. I want to reckon with the particular and unique challenges that black queer youth experience, both at home and everywhere else. Moonlight gives us that. And it gives us the gift of Teresa. She is like air. The antithesis of a stereotype, Teresa is not the around-the-way girl you expect to be the live-in girlfriend of a gold-grill wearing, child-saving drug dealer. She is the reverse of Chiron’s mother. But Chiron’s mother lacks the depth, until the end, to mark her as anything other than a bad mother. She is only redeemable through Chiron’s forgiveness.

The film juxtaposes the two female figures so that they are inevitably seen in opposition to one another, seemingly balancing each other out, and neutralizing black womanness in the film. We never see the two black women together or at the same place at the same time. In many films where the black woman binary exists, black women are visually separate, so that the distinction is clear. Teresa is good, Paula is bad.  They are diametrically oppositional characters. One breaks Chiron, while the other one mends him. Paula’s resentment and jealousy of Teresa’s role in her son’s life only further maligns her as selfish and territorial. Teresa’s infinite support and kindness mandates that Paula fail as a mother, while Teresa excels, though she has no children of her own (another common characteristic of “good” mother figures in film). Paula’s attempt at redemption, years later, feels as inadequate as Mary’s desperate plea to her daughter at the end of the film Precious. Too much, too little, too late. Once a bad black mother, always a bad black mother. The damage cannot be undone.

They are diametrically oppositional characters. One breaks Chiron, while the other one mends him. Paula’s resentment and jealousy of Teresa’s role in her son’s life only further maligns her as selfish and territorial. Teresa’s infinite support and kindness mandates that Paula fail as a mother, while Teresa excels, though she has no children of her own (another common characteristic of “good” mother figures in film). Paula’s attempt at redemption, years later, feels as inadequate as Mary’s desperate plea to her daughter at the end of the film Precious. Too much, too little, too late. Once a bad black mother, always a bad black mother. The damage cannot be undone.

“Bad” black mamas are common tropes in films where black women are scapegoated, in Moynihan fashion, as the precursor for pathology in the black family. Black mothers are blamed or implicated though rarely praised or celebrated. Working mothers are chastised for not being stay-at-home mothers; welfare mothers are demonized for not working; single mothers are blamed for not being sufficient “father-figures,”; married women are expected to want to be mothers; young mothers are vilified for unplanned babies; older mothers are harshly judged for waiting too long. Criticisms of black mothers are ubiquitous, even if and when they do “everything right.” These callous characters are commonly balanced by un-mother figures who compensate for the failures of biological mamas.

The role of the black mother is central to coming of age films, and are particularly important for LGBT coming of age films, where black youth must struggle with coming to terms with an identity that may estrange them from their loved ones.

For example, in Dee Rees’ debut coming (of-age) out film, Pariah, black mothers refuse to accept their daughters’ sexual identity, punishing them by withholding affection and acceptance. Li, the main character, is 17 and questioning her sexuality. Her best friend Laura, an already out lesbian, has been disowned, and is continually rejected by her mother throughout the film. Li’s mother, Audrey, cannot reconcile her religion with her daughter’s lesbian identity. As a result, she verbally, emotionally and finally physically abuses her daughter, who turns to a surrogate mother for affirmation, understanding, and eventually escape. In Rees’ film, the philandering father is the “good parent,” despite his patriarchal and toxic masculine tendencies.

Because of all of the ways Moonlight pushes and pulls at identity politics and filmic possibilities, I believe the film offers an opportunity and perhaps a responsibility to reckon with representations, and trouble not just black masculinity and queer identity, but black womanhood, specifically black motherhood in the face of progressive black masculinity. With few exceptions, progressive black masculinity in film only exists if black women are absent, silent or maligned. And vice versa.

Films with black woman protagonists have similar problematic representations of black men. In films where black women are strong and/or powerful, they are often presented as a threat to black masculinity, causing black men to reject and/or compete with them. In films where black men are vulnerable and/or progressive, black women are overbearing and shrewd, accused of emasculating black men and adopting black masculinity for themselves. (Think Tyler Perry movies, any Tyler Perry movie). In order for black women to be independent, powerful and/or lovable characters, they must survive and/or avoid the blatant misogyny of male characters, regardless of sexual identity and orientation.

The cultural conundrum around this phenomenon is something that can be considered moving forward. I don’t see the portrayal of black womanhood in Moonlight as a failure, because I don’t see Moonlight as a film about black womanhood. I do, however, think that future films that engage the topic of queer identity and masculinity might expand, complicate and re-characterize representations of black mothers, so that even if and when they are not positive forces in their child’s life, their characterizations are attached to context and history (alongside or in lieu of a stereotype).

All black mothers are not emasculating or unloving. I look forward to future depictions that include black mothers who love their children unconditionally and defend them fiercely. All black women are not flawless. I look forward to representations that allow black women to be redeemable without being self-sacrificing. All black women don’t want to be, and/or should not be mothers. I look forward to stories that humanize these women, allowing their children to be rescued before enduring irrevocable damage. All black life is not pathological. I look forward to more stories that chronicle the beauty of blackness, black love, queerness, masculinities, femininities, gender, fluid sexualities, inevitable redundancies, and motherhood.

As Lamar Wilson, one of the speakers at the film talk back summarized in his closing comments (I’m paraphrasing), the beauty of Moonlight is its refusal to bend to our expectations, its insistence that we question what we think we know, and its invitation that we challenge how we have been conditioned to feel (about the lives and bodies of black folk).

I’m going to relish in the light of this moon (the film is all the things) while I wait for the light of future suns, bringing more films, more characters, more characterizations, more representations, more (of) us. Sunlight soon come.

P.S. Go see this film!

P. P. S. And are you watching Queen Sugar? (another blog post, another day)