For your #TurnUp Tuesday pleasure, I thought I’d do a little Crunk theorizing today. As y’all already know, CRUNK is a generative term, a percussive term that centrally points to the kind of energy generated by putting disparate elements together like hip hop and feminism or black nationalism and feminism or crunk and feminism.

The kind of sonic expressiveness that encapsulates crunkness is heavily reliant on a percussion driven sound. So as we aimed to put the terms crunk and feminism together, we were interested in how the expressive culture of crunk could animate our feminism.

CRUNK Feminism puts the bass in your voice and the boom in your system. Our feminism makes you say it with your chest!!! It is a feminism that makes you move, a feminism that indexes a fundamental relationship to one’s body and one’s embodiment.

Crunk Feminism is feminism all the way turnt up! Feminism that is off the charts. Feminism that is lived out loud. Feminism that demands to be heard.

And it is that moment of (the) turn up, that signal achievement of being all the way turned up – crunk – that inspires this revisiting of what percussive feminism means and makes room for.

So first, a genealogy by way of a playlist.

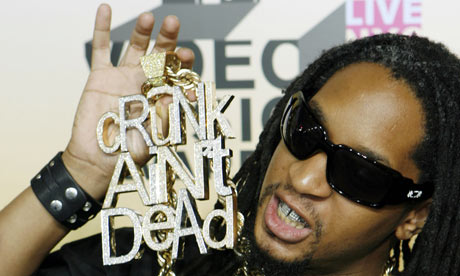

In 1994 – 20 years ago, I know! – Lil Jon released a Southern regional classic called “Who You Wit? Get Crunk!”

Though the innanets claim never to forget, there seems to be very little trace of this song until Lil Jon released it on an album in 1996. But I distinctly remember it more than two years earlier. So for this little exercise, consider my memory an archive of CRUNK. Suffice it to say, Crunkness is at least 20 years old, and prolly a little older, especially if you peep Andre’s line “I gots it CRUNK, if it ain’t real, ain’t right” on the late 1993 release of Player’s Ball.

Outkast is celebrating the 20th anniversary of their first album this year, with 40 festival tour dates. Make sure y’all check out the homie Red Clay Scholars phenomenal Outkasted Conversations series, for more on the musical influence and genius that is Andre 3000 and Big Boi.

1994 also saw the release of Notorious BIG’s first album Ready to Die, Da Brat’s Funkdafied, TLC’s Crazy, Sexy, Cool and the first major inroads of Hip Hop in the academy with the release of Tricia Rose’s groundbreaking academic study Black Noise.

But I digress.

Lil Jon and the Eastside Boyz refined that signature CRUNK southern sound and made it famous in the early 2000s with tracks like

Lil Jon’s Bia Bia and Put Yo Hood Up.

And of course here are a few of my other faves from the era

Bone’s Crusher’s Neva Scared; Young Bloodz If You Don’t Give a Damn; Lil Jon’s Get Low ; Dungeon Family’s “Emergency”

But peep:

More recently, Crunk inheres in joints like Roscoe Dash’s 2010 “All the Way Turnt Up,” 2Chainz “Turn Up,” and DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s “Turn Down for What?!” (below)

****************

To understand CRUNK is to understand how Hip Hop, in this case Southern Hip Hop, conjugates language in such a way that Black people’s relationship to it is less a corrupting and more an interpellation – or calling forth of language, the kind of language that allows us to call forth ourselves as (who) we are . Or rather as who we be.

Despite urban legends about CRUNK as portmanteau of Crazy and Drunk, in its most basic iteration it refers to infusing energy into a system so that it speaks the loudest, can be undeniably heard, and makes its most significant impact.

Get some CRUNK in ya system!!!

Crunk is both the past tense and the past participle of to crank. The onomatopoeic, hydraulic CRUNK calls forth that distinct sound of cranking up an old Monte Carlo like the one my mama had, or an old Cutlass. It’s the tale-tell UNHHHHHK… that infuses energy into the system.

To crank something is either to turn it on or to turn it up. And in the case of the turn up, the imperative to “crank it” means to turn it up so loud that you might bust your speakers. To turn it up so loud that it cain’t go no mo’. By way of a corollary –and perhaps a crunk-induced coronary– One can’t get CRUNK if one won’t turn up.

The turn up is a moment endemic to CRUNK. It cannot be understood outside of either the ontology or the technology of CRUNK.

One envisions a knob being turned –cranked—to its highest levels. The image is striking most notably because very few of us even have the kinds of radios that run with knobs anymore. To turn up the volume on things no longer requires us to crank a knob. Rather we touch an image of a button on a flat screen, run our fingers across a scroll wheel, or slide a knob upward. This kind of past-in-present understanding of crunkness, this tethering of the turn up to an image of a technological world rapidly receding, is similar as Crunkadelic says, to our clicking on an image of a floppy disk to save documents in WORD even though no one uses floppy disks anymore.

This using of our tense linguistic past to conjure both a present and future state of being tells us something about the incapacity and insufficiency of language to fully apprehend either the ontology or existence of Brown people. But it also points us to the genius of the African-descended. Such truths point us to the beat, that singular entity that allows us to smoothly and simultaneously occupy –and indeed become masters of– both space and time.

This is the ontological world of CRUNK, the world constituted through (the) turn up. When a car has been crunk, it is on, ready to go. When the music has been crunk, we are on and ready to go. There is no in-between state. The car is either uncrunk or crunk. So too with the turn up. Either things are all the way turnt up or they are not.

Crunk means to be all the way turnt up. It means to have turned up.

Turn up is both a moment and a call, both a verb and a noun. It is both anticipatory and complete. It is thricely incantation, invitation, and inculcation. To Live. To Move. To Have –as in to possess– one’s being. The turn up is process, posture, and performance — as in when 2Chainz says “I walk in, then I turn up” or Soulja Boy says, “Hop up in the morning, turn my swag on.” Yet it holds within it the potential for authenticity beyond the merely performative. It points to an alternative register of expression, that turns out up to be the most authentic register, because it is who we be, when we are being for ourselves and for us, and not for nobody else, especially them.

Lil Jon’s question “turn down for what,” then, becomes an existential question of the highest order.

To be black or to be non-white in the West is to live in a world that expects us to live in a state of being turned down, unobtrusive, inconspicuous, ornamental. We are to both turn down and tone down. Our presence is loud even when we are completely silent.

We should not believe the lie that turning down, that perpetual incognegro status, will reduce the severity of white supremacy’s impact on our lives. It’s reach remains uncurtailed, its view unobstructed. And

Your silence will not protect you. This is a truth we know. A truth Mama Audre left here with us. A truth that carries us again to the fundamental existential question Turn Down for What?

this was fun!

So glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for reading!

This is pretty much the best thing I have ever read

This is amazing. Thank you.

UGH. AMAZING POST.

Your silence will not protect you. Well said!