one.

I was defriended on Facebook this summer after a rather dramatic set of exchanges that took place publicly and I recently began to think about that defriending because I wanted to consider how mishearing and misreading were the grounds through which a purportedly critical analysis of my position was given and how that mishearing and misreading allowed the individual to feel good about himself once he finally clicked “unfriend.” Mishearings and misreadings are often foundational for argumentation, and though one’s argument may or may not, in fact, be correct, because of the straw man against which they contend, incongruity is often the result in such conversation. I reposted a status written by Mark Naison that argued, regardless of political affiliation, regardless of the person for whom people would vote into presidential office, that grassroots organizing must, of necessity, take precedence, given the economically unviable world in which we live:

”No matter who wins the next election, the US is likely to become a poorer, crueler country with leaders in every walk of life seeking to protect their own advantages while demanding sacrifice from those who work for them, or depend on the programs they offer. If there is going to be kindness, generosity and compassion, it is going to have to come from people ‘on the ground’ and be reflected in how they help one another when they are in trouble. [A]nd how they share dwindling resources.”

The individual that eventually defriended me responded by saying it was sad that I was cynical, that I should have hope and belief in the “political process” and that I should simply join Team Obama. I resisted a lot of his language because Naison’s assertion was not about the limited category that we call politics, as such. It was about how we will need to build coalitions with folks from all walks of life, how the hoarding and greed of the economically privileged class squanders resources for the “least of these,” making of us all dependent on one another. I was reminded of this exchange because of the urgency of Naison’s words ringing ever more true today: his words were a call to sociality, to being together with others that is likewise the condition of emergence for imagining a new world, a world wherein we share together in resources, wherein we share together in life and love through generosity and compassion.

Naison’s words reverberate, indeed, given the fact that the Chicago Teacher’s Union held a strike that lasted seven days in September this year, teachers fighting for better wages, better work hours, medical and mental health staff for students, better accommodations, books on the first day of class and a reduction in the weight given to standardized testing for teacher evaluations. Many folks on the left agreed with the CTU’s position. And when a candidate for president in 2007, President Obama promised not only to support unionized labor, but to put on his comfortable shoes to march with unions for better labor conditions. However, the striking in Wisconsin and the CTU illustrates the ways Obama wanted nothing more than the CTU strike to end quickly and quietly. In other words, whatever the teachers would receive would be gained through their own collective organizing with no support from the one that once promised to be with them.

Naison’s words reverberate, indeed, given the fact that the Occupy Movement, under the guise Occupy Sandy, is one of the primary means by which folks in New York City are receiving resources after Hurricane Sandy. The Occupy Movement was certainly dismissed by both major political parties, with the Republicans thinking the lament of the 99% vacuous and tantrum, with the Democrats attempting to coopt the critique of the current political economy by attempting to “Occupy the Vote.” Funny, then, how it has been the support given by the Occupy Movement that gathered quickly and rose to the occasion of the current crisis, delivering meals, clothing and medical supplies.

Naison’s words reverberate, indeed, given the fact that Wal-Mart workers are calling for a strike, organized action against the superpower because of its varied, storied, many abuses of the workers there – everything from ensuring workers do not have schedules long enough to receive healthcare benefits, though forcing workers to labor extra “overtime” hours, to the general belittling and lampooning of workers as “stupid” and “dumb” by management. Similar actions are likely to proliferate rather than come to an end because we live in a world of economic collapse, the refusal to take Climate Change seriously during presidential electoral debates, the privatization of public services and the general assault of organized labor.

Indeed, if we are to thrive in the world, we will achieve this through collective organizing, by another politics, a politics that contends with and against simple assertions of “political processes.”

two.

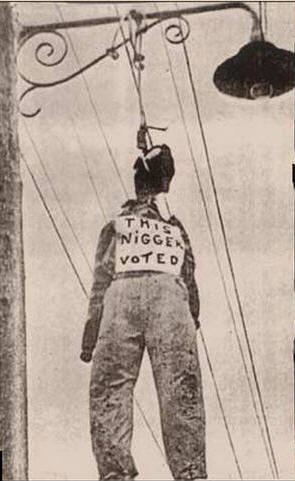

(Trigger Warning: Lynching Image)

Various reminders to “get out the vote” last week invoked the category of “ancestors” as the reason for such urgent action. It is, indeed, true that the history of suffrage movements in the US document various marginalized groups contending for the ability to vote in local, state and national elections, attempts to participate in the representational political form that is our republic. I was uneasy by the invocation of ancestors, of family members who once could not vote, as the reason why we must participate today. It is true that suffrage was, and is, held from peoples throughout the history of the US with violence and perpetual violation. The underside of such assertion was the implied critique that to not vote, to intentionally abstain, is mode of dishonoring the same past. But there were other ancestors, other modes of collective – and thus political – organization that did not desire the thing, we might say, was withheld them.

“‘Slaves and maroons from various plantations met regularly in the cipriere,’ Gwendolyn Mildo Hall writes, ‘Huts were built, with secret paths leading to them. A network of cabins of runaway slaves arose behind plantations all along the rivers and bayous.’ Much of the social life of the city’s slaves became concentrated in the swamps where they could talk, dance, drink, trade, hunt, fish, and garden without supervision. The settlements were hidden away, but they were also integrated with the life of the city. Unlike in some places in the United States, these maroon communes had many women and children” (Disturbing the Peace, 62).

The ciprieré communities secreted from local plantations, maintaining a relationship to spaces from which they escaped, but established new patterns of behavior and aesthetic interventions for protection and peace. Setting traps, navigating the swamps, having sex, singing, raising children, eating – all these were aesthetic practices that always and likewise had to be forms of preparation. Maroons needed be ready at a moment’s notice for encounter with the political world of the exterior that would bear down on them and produce violence against them. Each practice, therefore, was a likewise preparation for the possibility of the threat of violation; each practice, thus, highlights the ways in which interventions always likewise have an aesthetic quality and theoretical underpinning. We might say that the CTU’s ability to organize quickly, that Occupy Sandy’s ability to gather and disperse resources at a moment’s notice, was but another figuration of the extrapolitical aesthetic practices of marronage, a way to be in worlds but not of them, a way to respond to needs as a critique of the institutional structures that create such need in the first place.

Michelle Wright writes about how “[m]ost of the Social Sciences and Humanities derive their standard notion of time from physics – specifically Sir Isaac Newton’s notion of time as a fixed constant, linear in its movement – physics itself abandoned Newton’s belief a century ago” (73). That which is considered space and time in Social Sciences and Humanities emerge from particular philosophical and theological movements. Such that interruption of an aesthetic practice offers a general critique of the normative political sphere, such that black power disturbs historical narratives and the ease with which ancestry is sometimes deified, such that blackqueer atemporality troubles binaries of rocking or mocking votes. The interruption that is black power, that is black feminism, that is the blackqueer aesthetic, also disassembles space as well. Such that it becomes increasingly difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish the Prison Industrial Complex and the general militarization of police power in cities like New York City, Los Angeles and Oakland in the elusive borders of something called the United States from the heightening of militaristic power that terrorizes in Pakistan, Yemen, Libya.

So while it is true that abstention from electoral politics does not, of necessity, protect, attending to another ancestry, the history of marronage, perhaps presents us with other ways to think abstention-as-protection, where protection was not about the participation in, nor the replication of, the spaces from which enslaved folks escaped, but was about the desire to be left alone, to organize and care for one another without the imposition of the state. In our world, in our interconnected cyberculture, the local becomes ever more important and Occupy Sandy, as a figuration of ciprieré marronage, is an illustration of the quick, intense and intentional emergence of sociality to current local conditions. And maybe the local is all we have.

three.

I was defriended last week on Facebook, either the day before or of Election Day, for reasons similar to the opening story. I posted writing by Summer McDonald about her decision to not vote in this year’s election. I was confused not by those antagonistic to a decision to not vote, but that people were upset about the audacity to declare the decision of abstention in the midst of all the enunciations of support for the red, blue, green or independent parties. I hadn’t read too many things declaring abstention as a choice, so I’m still waiting for receipts about why this limited group produced such a seemingly loud response.

I have attended a church locally in Durham for roughly two years (and I will return once I get out of job market / finishing dissertation … heaven. lol), though I am a self-proclaimed agnostic. Something about the sociality of being together with others was, and is, important to me, though I oftentimes disagreed in some pretty huge ways with things being said. There was something about struggling with others, while struggling within myself, to make a new world inhabitable by more folks than just ones generally deemed acceptable. But sometimes, struggle is too much and lines are drawn in the sand. The first time I walked into a church in Durham four years ago, as I took my seat in the very back of the church, the pastor quickly began bespeaking the horrors and sinfulness of being gay. And I don’t even think I wore my rainbow headband that day. But I picked up my keys and walked out as quickly as I walked in. And one of the ministers, presumably, ran out after me to ask who I was and why I was leaving. “I’m a gay dude…but I’m ok with it. And your pastor is just wrong,” is what I told him to which he replied, “give me your number so we can talk about it later.” Gotta love the contradictions.

As a cisgender gay dude that grew up in Pentecostal churches as a musician, songwriter, singer and preacher, I am well acquainted with heteronormativity, sexism and homophobia that run in a lot of religious rhetoric, such that I understand when other folks choose to abstain from participating in religious communities. For them, religious ritual does not counterbalance the at times violent rhetoric used to dismiss large groups of folks. For them, religious ritual is something that they find otherwise and elsewhere than the church … and in many ways, they create gatherings in spaces that are just as sustaining and important. I think I’d be justified in never going to another church in my life, and I’m ok with that. But I also get why people continue to go back, with hope. We need not denigrate either position, as both emerge from a desire to be and be together with others. I do not dishonor my parents, my former churches nor my old way of life when I use the queer theoretical ideas I learned in elite, private universities just because I learned them in those elite, private places. You do not dishonor your ancestry if you choose to live in the world in ways that honor what you believe allows you to stand in your truth, to be transparent in a world that would have of us all to be fearful and afraid. Rather, we honor folks when we engage them, even when we disagree loudly.

(sigh) Collective action at the local level also means getting involved in your local political party, so you can affect the decisions not only there, but in the longer run the state and national agendas.

Not voting for any “principled reason” just puts you in the category of “safe to ignore” by any politician and political party. If you can’t be bothered, neither can anyone else.

I’ve got to co-sign on your comment there. Truth.

Norbrook’s comment is so accurate.

“So while it is true that abstention from electoral politics does not, of necessity, protect, attending to another ancestry, the history of marronage, perhaps presents us with other ways to think abstention-as-protection, where protection was not about the participation in, nor the replication of, the spaces from which enslaved folks escaped, but was about the desire to be left alone, to organize and care for one another without the imposition of the state.”

The problem is that many PoC are NOT being “left alone” by the state; the state refuses to let PoC alone. In the meantime, we need to fight by all means necessary to protect ourselves.

As a cis queer WoC, I felt that too many of my rights were on the line this election season. And while I did not respond to every category on my Florida ballot, I did vote in my interests for the ones that would have most immediately affected me, whether I agree wholeheartedly with the implications or not.

Thank you for this, Ashon. Much appreciated.

I didn’t know about the cipriere.. Wonderful inclusion of an endearing and enduring site of resistance to white supremacy and slavery.

I love this. It is important to think about political participation in a number of ways, including those outside of the conventional political process/system (voting, GOTV efforts, PACS, etc). Think about the simple notion of sitting on a new seat on a public bus – expanding/producing the very space the conventional political process excluded you from, without fully relying on the conventional political process to affect change. Wonderful and insightful piece here. -AD

To use a long ago description that means much to me, I RESONATE with your essay. My approach to religious expression seems much like your own, with differences, I did not grow up in a pentecostal-black church, just nominal mainline Protestant, albeit Southern “Colored.” I offer you comfort in realizing that your critics are reacting in fear, by name calling, and you do not deserve to fall into their narrow focused world.

I have to be honest and admit that I can hear and think about this because I feel safely on the other side of Tuesday the 6th. It is interesting that due to the state I live in I can honestly state that my vote did not make a dent in the Georgia decision. But the salient connection between the right/responsibility to live in truth in religion and politics I can get behind even though it is unsettling. I feel like the religious choice to attend or not attend church has individual ramifications whereas the political choice to engage or not engage on a range of levels has collective ramifications. But even as I write this I know it is too simple. I do not attend church but was raised across a Christian spectrum, the local political landscape shakes beneath my feet with contradictions, and national politics feels like football (wasted money and all) but there is a fear healthy/unhealthy about engagement with politics that does not register the same as engagement with religion.

Thank you for this eloquent essay. It brought up a lot of holes in my thinking.

It is sad, but there is some humor in posting about how everybody needs to work together and exhibit kindness and teamwork on the ground, and then getting unfriended over it.

I just briefly want to request that anyone who is abstaining from voting on principle please do so on the ballot at the polls – which I know sounds counter-intuitive.

If you go to the polls to declare your abstention, it’s actually recorded as an abstention, vs an absence. You are marked “present”, you can write in your own name on the ballot, or the name of someone else you think would do a better job than the listed candidates (please choose someone eligible to serve), or you can write “this space intentionally left blank”, or “none of the above”.

Your refusal to vote for the people named on the ballot will then be recorded.

This is important, because abstaining through absence is indistinguishable from absence for other reasons, and thus cannot be recorded as a protest.

Also, there are other items on the ballot aside from elected offices.

Thank you for hearing me out on this.

This election brought out the ugliness in everyone. After the election I lost a few friends and over the summer I posted a conversation I had with some of Romney supporters.

i thought this article really got to the core of so much that gets passed over in discussions of politics and even racial justice organizing. that in the end, it is about creating the nurturing communities and relationships we need as human beings. and i think american society has so much to learn from its communities of color and immigrant communities, as well as societies in different parts of the world that have found ways to make community work better for people’s needs. the most frightening thing to me about obama’s neo-con foreign policy stance and love for global capitalism is that it will only help to continue erasing those precious realities.