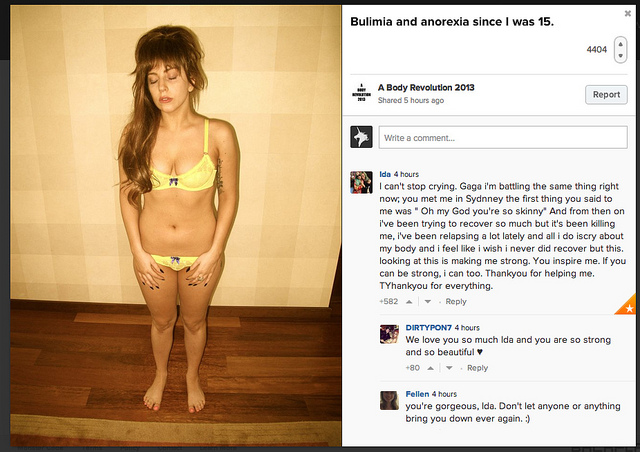

Earlier this week, Lady Gaga launched a campaign, via her website, called Body Revolution 2013. An attempt to reclaim the conversation from the folks in the media who were writing about Gaga’s body as seen in a few recent photos, wherein she looks a little larger than she usually does. (I’m not linking to those photos and articles, Google if you must.) Essentially, these (assuredly svelte) members of the media were calling Lady Gaga fat. Gaga, in a missive in which she’s both vulnerable and angry, spoke out about the fact that she’s been dealing with anorexia and bulimia since the age of 15. And as only a global susperstar can, she’s re-energized a conversation about the challenges that young people, young women and girls in particular, are facing as they struggle to accept their bodies in a world that is hateful and cruel. These struggles are both external (how do others perceive me?) and internal (what do I see when I look in the mirror?) and they are nothing new. But a dose of celebrity adds another dimension to this already pressing issue.

Earlier this week, Lady Gaga launched a campaign, via her website, called Body Revolution 2013. An attempt to reclaim the conversation from the folks in the media who were writing about Gaga’s body as seen in a few recent photos, wherein she looks a little larger than she usually does. (I’m not linking to those photos and articles, Google if you must.) Essentially, these (assuredly svelte) members of the media were calling Lady Gaga fat. Gaga, in a missive in which she’s both vulnerable and angry, spoke out about the fact that she’s been dealing with anorexia and bulimia since the age of 15. And as only a global susperstar can, she’s re-energized a conversation about the challenges that young people, young women and girls in particular, are facing as they struggle to accept their bodies in a world that is hateful and cruel. These struggles are both external (how do others perceive me?) and internal (what do I see when I look in the mirror?) and they are nothing new. But a dose of celebrity adds another dimension to this already pressing issue.

Several have written about the potential impacts of a celebrity naming their struggles with eating disorders – some think it’s helpful, others don’t and others find it complicated. There’s something both valuable and limiting about a celebrity like Lady Gaga coming forth. On the one hand she embodies a relatively conventional ideal of beauty, being young, thin and white. On the other hand, it’s notable that these extremely narrow conventions of beauty are insufferable by almost ALL people, Lady Gaga included. I won’t (re)litigate the conversation about the value of her admission here. Generally, I find that anything that breaks into the mythology of celebrity is at least minimally useful, because it allows us to disrupt the damaging messages that come from and through our obsession with fame and fortune as measures of worth. (Here, I mean “worth” the existential sense, as well in the context of capitalism. Lady Gaga is very well compensated for her art, which is entangled with her “image.”) So, yes, a “body revolution” in which we flaunt and expose our “perceived flaws” and “make our flaws famous, and thus redefine the heinous” in order reclaim our sense of self from the media machine is a good thing. But there’s something else going on here.

In this charged context, what does it mean to be beautiful? And what does it mean to be ugly? And another question, to complicate the binary between beauty and ugliness, because binaries never serve us well: what does it mean to be invisible entirely? Or hyper-visible?

We, as the social creatures we are, long to see and be seen. And to be seen as valuable, worthy of love, and affection, and deserving of care, personal, interpersonal, social and political. There are many measures of value, and they all depend upon being “seen.” So, this question, of what it means to see and be seen, is rooted in understanding the pain and agony of people around the world who struggle to see themselves and to be seen by others as valuable. This is about those little girls, who look at themselves in horror and anguish, feeling worthless if nobody calls them beautiful. And in the cases of young girls and women of color, seeing themselves as inherently less valuable. In this context, answering the question “what kind of body revolution do we need?” is urgent. A lot is at stake.

Jessica Valenti’s argument in favor of embracing “ugly” comes from the notion that we must confound traditional notions of beauty and the social value that comes with them. In light of the emergent trend in which young girls get plastic surgery so as to avoid bullying and shame, Valenti argues that there are virtues cultivated from resisting these notions, and embracing the anger and dispossession they engender. We fashion the world in our own image, then, and refused to succumb. I find this argument compelling, to be sure. I am routinely pissed off about the way beauty is defined and described so as to exclude me, and so, so many others. And I certainly derive strength from that rage.

But then, I also have to pause. I notice my discomfort begin in earnest whenever we have conversations about beauty and body image that do not include in intentional analysis of beauty as something that lives right at the intersection of race, age, ability, gender and sex. It’s not an expendable luxury here, to name these things. For women of color, the notion of embracing and seeking the upside of ugliness is a complicated task in the fight against invisibility on one hand and hyper-visibility on the other. Think of how transgender bodies are erased by the various industrial complexes in which we are mired. CeCe McDonald’s very identity is rendered irrelevant when she, a trans woman, is incarcerated and placed in a men’s detention facility. Think about the double-sided scourge of Islamophobia and misogyny that Middle-Eastern and South Asian women face daily. Think about the legacy of slavery in which black women’s bodies were treated as commodities with categorically dehumanized desirability, worth and beauty. Think about the research telling us that women with disabilities are more likely to suffer domestic violence and sexual assault than women without disabilities. Think about the incessant slut-shaming and victim-blaming that characterizes our national conversations about violence against women.

In these contexts, what is the upside of ugly? Or as Lady Gaga beseeches us to, how do we “redefine heinous?” When “ugliness” carries the threat of violence and disenfranchisement, what does it mean to embrace “ugly?” For a person whose body is dehumanized and positioned as the very definition of undesirable, is it possible to “redefine heinous?” Perhaps, but its not neat. To do so we have a lot to dismantle. To do so we have to dwell in the intersections. Beauty and ugliness are not two sides of a coin, they are the same side of the same coin.

To dismantle them involves thinking through what the other side of that coin is. What does is mean for us to see each other as fully human? And as singularly and collectively valuable?

This project is different than the project of asserting that we are all beautiful in our own way (like those Dove “Campaign for Real Beauty” campaigns implore of us). It is different than embracing the character building elements of being seen as “ugly.” It involves conversation about what makes us human and valuable. And it must also include a re-definition of both “beauty” and “ugliness” alike.

Maybe THAT is the body revolution we need.

FYI Dove is owned by Unilever, who owns Fair and Lovely, a skin whitening cream sold in East Asia.

Don’t forget Africa…

Reblogged this on Delusions of Self & World Improvement and commented:

Once again CFC is on point. READ THIS.

Thank you for writing this. It takes a lot of energy to cultivate something that speaks to the human condition, especially the desire for love, acceptance, and visibility. Again, thank you.

“On the one hand she embodies a relatively conventional ideal of beauty, being young, thin and white” is a questionable statement. Is she really trying to refer to the conventional idea of beauty by shaving eyebrows? Or is she trying to resist those body conventions represented by the system of the Hollywood stars? Isn’t she fighting that system of the Hollywood/ Fashion industry/ European beauty conventions by resistance and slow implementations of new aesthetical criteria towards human body? Isn’t she a speaker of the Baudrillard’s “silent majority” that starts moaning senseless and ugly speech through reality TV and social networks? Isn’t she directly pointing by her very name to the anal fixation of the oppressed masses by rather obvious reference of her name to “kaka” commonly meaning “shit” in the majority of languages? Along with “oops, I did it again” she sends of a message of infantility and shitty reality in which obesity has to be taken as smth normal just for the sake of protecting Empire’s social and political status quo. By sending this message she’s maintaining individual inabilities for self-transformation and in this way prevents ugly, unsatisfied and dead-ended from liberation from the system’s oppression. Being part of the System/ Empire she’s executing social and political order. The question is who’s orders do you perform by writing/ reading such unsubstantiated articles?

i’m waiting for someone to admit that beyonce’s boastful and extreme weight loss methods are just eating disorders by any other name.

I think you’ll be waiting a long time for somebody to admit that.

Sorry I find her terribly convoluted and fake in about all she does.

I worry that this statement in itself is perpetuating sexism – I’ve never heard this descriptor used for a male celebrity before.

Eesha: YES!!!

Are you familiar with Mia Mingus’ keynote at the Femme of Color Symposium last year or the year before? Before Jessica Valenti…who can engage in extremely problematic behavior….wrote her piece in response to the young woman who was bullied, Mia spoke about embracing the ugly and that THIS is what is liberatory, thus moving past the ” fat/ short/black/disabled/queer, etc, etc, etc” is beautiful too!!”. Of course, Mia can speak for herself..http://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/08/22/moving-toward-the-ugly-a-politic-beyond-desirability/

I love MIa’s piece, Mandisa. I really appreciate how she chooses the terms with which she identifies – and her discussion of why she doesn’t identify with the term “femme.” To me, it’s more than just a re-appropriation of “ugly” that she’s calling for — It’s a redefinition, and I love redefining things!

Staten Island Borough President James Molinaro recently jumped into the fray as well, calling Lady Gaga a slut. He is such a sexist asshole.

i think critical in the dismantling of beauty constructs is a re-definition of what makes us valuable. as long as women are taught that our power lies in our ability to attract a man and that only some women have the ability to attract and that all others lose that power by degrees along lines of race, weight, ability, sexuality, etc., any body revolution will be powerless. and as we have the conversation i think we, as women, need to recognize our power and privilege or lack of that power and privilege in the conversation. the closer we are to the beauty standard, the more power and comfort we have with which to challenge it. lady gaga can do what she’s doing because she has lots of body privilege. i am a white woman; i am not thin, but am only softly rounded. i talk about redefining beauty often, with lovers, friends, the young girls in my life. a couple of years ago i made the decision to let the hair on my chin grow out. but i have to recognize that my ability to make that choice comes from the violence done against women who dont look like me: done against women of color, women of different body sizes, of different abilities, different sexualities. i think the dialogue around dismantling beauty standards must inherently be connected to a more honest conversation about white female privilege. and it is not the work of this collective to initiate that conversation, but my own work and the work of other white women to stop hiding behind the evil of white male privilege and begin challenging our own. i am excited about both of these conversations and how they are entangled. thanks for this piece and for how it initiates so many conversations.